Aloha fellow humanoids!

I know a few weeks back I said I’d try to get a recording of my speech at VAC2016 to show you guys, but unfortunately I haven’t been able to. Sorry about that.

Instead, here’s the next best thing; the official script! I know it’s not quite as impressive, but hopefully it gets the job done. Enjoy!

Good morning!

Like the giant screen says, I’m Max, I work for the I CAN Network as a classroom mentor and editor in chief, and I’m here to talk about video games, autism, and how neither is quite as scary or negative as a lot of the media would have us believe.

In the interest of disclosure, I’m on the autism spectrum myself, and yes, video games are something of an interest of mine, just as they are for many others on the spectrum who I know and work with.

So let’s start with the medium itself. Video games as we know them originated in the 1970s, and at the time, they were basically electronic toys. And that’s an image that has stuck, even to this day.

I would argue, however, that in 2016, this is an obsolete stereotype, and that to pigeonhole all video games as toys is a bit like saying that all food is nothing but cellular fuel, with no other purpose than to keep us alive. Because just as food plays a myriad of social, cultural, and even medicinal roles, video games as they exist today encompass a wide range of forms and functions, from complex storytelling, to artistic expression, to shared social experiences.

Now, I’m sure most of you won’t be surprised to hear that people on the spectrum very often have an affinity for gaming. Among both my colleagues and students, it’s probably the single most popular “special interest” that comes to mind. So why is that? By the way, just so I’m covered, this gentleman, who you may recognize, is property of Nintendo.

Well, first of all, gaming can be a great way of relieving stress. A virtual world can be a “safe space” of sorts. School or the workplace can be frightening, chaotic, and it just seems to make no sense sometimes. Games, by contrast, have a degree of predictability and logic than can be very comforting.

In real life, you never quite know how people will react, or what will happen next, and that uncertainty can be terrifying. There’s that constant anxiety, that feeling that at any moment things will go pear-shaped. Video games allows us to take a break from that, because in a video game I know that if I press this button, this happens, or if I flip this switch, that happens.

Games can also be a welcome distraction from unpleasant thoughts. I think it’s fair to say that most of us have that thing we do to take our mind off things that upset us, whether it be a good book, music, television, or a glass of wine. Such diversions can be very valuable coping tools, as they can act like the scab on a healing cut, providing a sort of temporary protection to give our bodies and our minds time to recover.

A person on the spectrum may come home from school or work, and they might be like a pot that’s boiling over, just bubbling with stress that’s been building up all day. What they may need is something that can take the pot off the boil for a bit, so that it can cool down, and for a lot of us, video games do just that.

Another potential benefit of video games is that they can provide an outlet not just for one’s stress, but also one’s creativity. There are many games today that instead of ushering the player through a predetermined obstacle course, instead act as a canvas for the player’s own creative expression. They provide you with the tools, and then let you loose to do what you want.

Perhaps the quintessential example of this is Minecraft. Personally, I’d be very interested to know what proportion of Minecraft players are on the spectrum, because I suspect the number would be very interesting. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the game, (I dunno, maybe you’ve been on Mars for the last 5 years) it’s basically a sophisticated virtual Lego set, where the player harvests materials then uses them to build whatever they want. And some of the things I’ve seen people build on it are just amazing. I know this one kid, this really gifted young guy, and he loves Steam Trains. And he actually built a working steam engine in Minecraft, in his spare time. It’s a lot like building physical models or Lego sets as a hobby, except it’s considerably cheaper.

Sometimes, it’s not a specific game, but rather the medium itself that can serve as a creative canvas. The software tools for building a video game have never been more accessible and easy to use as they are today, and many people on the spectrum now make their own games, in much the same way as others might write a book, or a paint a painting. Not only is this a way for them to express their creativity, but in a world where video gaming is now a bigger industry than Hollywood, those coding skills could come in very handy someday.

Gaming can also be a socializing aid. One of my favourite stories in this regard is a young lady I know, a friend and colleague of mine, who really struggled with how to connect with other kids when she was in primary school. Not only was she very shy, but she just couldn’t seem to find any common ground with the other kids. Then one day, during the lunch break, she saw one of her classmates playing Pokémon on their Gameboy. And suddenly, there it was, that mutual interest, that common ground that they could bond over. That broke the ice, and that’s how she made friends at school for the first time.

And there’s multiplayer, where people can play together, either competitively or cooperatively, turning the act of playing itself into a shared social experience. A recent example of this is something you may have noticed happening in public parks over the last month or so. I’m talking, of course, about Pokémon Go; which for those of you who weren’t born in the 1990s, is a mobile game, which encourages players to get outside, explore their neighbourhoods in search of Pokémon, and along the way, meet other people who also play the game. Several people I know have already made new friends this way.

Basically, gaming can provide a familiar and comfortable environment in which to develop one’s social skills.

So if you have a kid on the spectrum who’s really into gaming, for example, a great thing to do is see if there are some games they play where you could join in, and play with them. Now, naturally, a lot of time they’ll want to play alone, because gaming can be their escape from having to deal with people, (and, let’s face it, their parents) but by offering to come into their world and participate in something they enjoy, on their terms, you can kind of meet them halfway, and spend time together in a way that’s comfortable for them.

Another factor that shouldn’t be overlooked, role that gaming can play in one’s social identity. A lot of kids on the spectrum can feel undervalued because they may not be the great at sports, or conversation, or a lot of things that denote social status in the schoolyard. They can often feel as though they’re not good at anything, that they have nothing to offer. But if they’re great at a video game, especially one with a multiplayer component, then among those who play the game, they’re a rock star. Everybody wants to have them on their team. Instead of always getting picked last in PE, people are fighting over who gets to have them on their side. And that sense of being valued and respected for their abilities can be an immense boost to one’s self-esteem.

Now, as with a lot of really awesome things, when it comes to gaming, moderation is key. I mean, broccoli is generally good for you, but if all you ever eat is broccoli, probably not a great idea. Similarly, it’s fine to have a best friend, but if you only have one friend and base your entire social life around that one person, again, it might not work out so well.

Gaming can be one avenue of social connection, but it should not be the only one. It should be a supplement to offline interaction, not a replacement.

Also, and this may sound a bit old school, but if we’re talking about kids, I think it’s important to set boundaries. For example, they can play games, but only for two hours a day. Or they can play games for an hour after school to calm down, but if they want to play for longer, they have to earn game time by, for instance, doing their homework.

A common question is, where do you draw the line? I would answer that by saying that it becomes a problem when it becomes a detriment to other areas of one’s life. One way this can be nipped in the bud is to ensure that does not become a dependency; for example, schedule a day out that’s technology free, so that they learn to cope without it. They can play when they get home, but for now, we’re here at the zoo to see the animals, not to play Candy Crush.

To return to the broccoli analogy, gaming should be treated like one food group within a balanced diet.

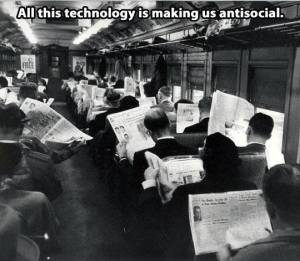

The media likes to portray gaming as something of a brain drain; a negative, corrupting influence, kind of like how television and rock and roll were portrayed when my Mum was growing up. I’d argue that reality is not so black and white, that almost everything in life has its positive and its negative aspects.

And while it’s certainly important to manage and minimizes the cons, I think it’s also very important to leverage the positives. Video games are here to stay, and so is autism. And I know from personal experience that the two can get along magnificently.

Thank you.